Homosexuality: When ‘Discernment’ Leads to Disaster

|

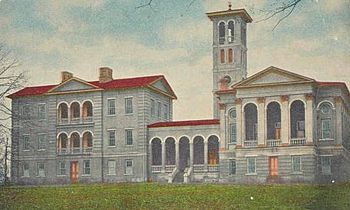

| English: Furman University - old campus, Greenville, South Carolina Postcard - cropped (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

The

historic First Baptist Church of Greenville, South Carolina, announced in May

that it would declare itself be “open and welcoming” to all people and that it

would allow same-sex marriage and ordain openly homosexual ministers.

The move came after the church had undergone a “discernment”

process under the leadership of a “LGBT Discernment Team.” That team brought a

report to the church’s deacons, who then forwarded it to the congregation. The

church then approved the statement by standing vote.

The statement is very clear: “In all facets of the life and

ministry of our church, including but not limited to membership, baptism,

ordination, marriage, teaching and committee/organizational leadership, First

Baptist Greenville will not discriminate based on sexual orientation or gender

identity.”

The Greenville News told of the congregation’s discernment

process and then introduced its news story like this:

“Would the

congregation be willing to allow same-sex couples to marry in the

church? To ordain gay ministers? To embrace the complexities of

gender identity? In an evangelical church born in the antebellum South?

Whose founder more than a century and a half ago served as the inaugural

president of the Southern Baptist Convention? Here, in

Greenville? The answer to each was ‘yes.’”

The congregation, now more than 180 years old, is one of the

most historic churches in the South. It participated in the founding of the

Southern Baptist Convention in 1845 and its pastor, William Bullein Johnson,

became the SBC’s first president. The church was largely responsible for the

birth of Furman University and its old “church house” became the first home of

The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in 1859. Few churches in the South

can match its historical record.

Nevertheless, First Baptist Greenville and the Southern Baptist

Convention had moved in very different theological directions in the last

quarter of the twentieth century. The church was moving steadily in a more

liberal direction and the Southern Baptist Convention was moving to affirm the

inerrancy of Scripture and a far more confessional understanding of its

identity.

The church and the denomination were set on a collision course,

and the congregation voted to withdraw from the Southern Baptist Convention in

1999. If that had not happened, the SBC would have moved to withdraw

fellowship on the basis of the church’s announcement in May. The denomination

has adopted a policy of withdrawing fellowship from any church that affirms or

endorses homosexuality.

By the early 1990s, it was clear that the historic church and

the denomination it helped to establish were operating in different theological

worlds. The Conservative Resurgence in the Southern Baptist Convention met

stiff opposition from many old-line churches like First Baptist Church in

Greenville. The Greenville church included many faculty members from nearby

Furman University, which also separated itself from the South Carolina Baptist

Convention.

The central issue of dispute was the inerrancy of the Bible. The

more liberal faction in the SBC affirmed that the Bible is “authoritative,” but

would not affirm inerrancy. Conservatives focused their arguments on the

necessary affirmation that the Bible is completely without error. Both sides

knew that the issues at stake ranged far beyond inerrancy, but both sides also

knew that inerrancy was the central axis around which all other issues

revolved.

On the masthead of the church’s newsletter announcing the report

of the LGBT Discernment Team, the church states: “We believe in the authority

of the Bible.” But the church’s affirmation of biblical authority did not

constrain it in any way from rejecting the clear teachings of Scripture or from

employing interpretive arguments that relativized the authority of the biblical

text.

Having abandoned and rejected the inerrancy of the Bible, the

congregation has no real means of affirming the authority of Scripture as

anything more than an historic point of reference — inspired in some way and

authoritative to some degree.

This is one of the central lessons now revealed two decades

after the Conservative Resurgence in the Southern Baptist Convention had gained

control of the denomination. The moderate-to-liberal faction in the SBC is now

affirming theological and moral positions that the leadership of that movement

would have condemned at the height of the controversy. The old liberal wing of

the SBC is marching steadily left, and the new generation of more liberal

leaders is pushing far beyond where the older leadership of their own movement

would have gone.

Evidence of that is seen in the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship,

a group that broke away from the Southern Baptist Convention in the early

1990s, rejecting the affirmation of biblical inerrancy. On May 9, 1991, the

Cooperative Baptist Fellowship adopted an “Address to the Public” that

explained why the group had separated from the SBC. “Many of our differences

come from a different understanding and interpretation of Holy Scripture,” they

said. “But the difference is not at the point of the inspiration and authority

of the Bible.” They went on to state clearly: “The Bible neither claims nor

reveals inerrancy as a Christian teaching.”

Significantly, the claim that the difference between the SBC and

the CBF was not over the inspiration and authority of Holy Scripture is

undermined by the document as a whole. While the SBC and the CBF may both

affirm the inspiration and authority of the Bible, these are not equivalent

affirmations. If the inerrancy of the Bible is not affirmed, plenary verbal

inspiration is also not affirmed, nor is the authority of Scripture affirmed as

extending to its very words. Moderates in the SBC generally affirmed a

“dynamic” model of biblical inspiration that extends to the ideas of Scripture

rather than to its words. This means that the Bible, when claimed as authority,

is a collection of inspired ideas and that the actual words are not, in

themselves, binding.

That explains how, in one generation, more liberal churches have

reversed themselves on the question of homosexual behavior and relationships.

Just one generation ago, virtually all of the churches now in the CBF clearly

affirmed the sinfulness of homosexuality. Now, many are moving to affirm

same-sex marriage and to ordain gay ministers.

The lesson — once a church or denomination is untethered from

the inerrancy of the Bible, there is no brake on the relativizing effects of

cultural pressure.

Interestingly, one key question now is whether the Cooperative

Baptist Fellowship can survive this transformation intact. A younger generation

of leaders is pressing forward with the full normalization of homosexuality,

acceptance of same-sex marriage, and ordination of gay ministers. The CBF,

however, while embracing many churches that have taken such actions, does not

hire openly-gay staff. In 2000, the CBF National Coordinating Council adopted a

policy that states: “Cooperative Baptist Fellowship does not allow for the

expenditure of funds for organizations or causes that condone, advocate or

affirm homosexual practice. Neither does this CBF organizational value allow

for the purposeful hiring of a staff person or the sending of a missionary who

is a practicing homosexual.”

The CBF is now set on a collision course with its own rising

generation of leaders. They are not going to let that policy stand. How can

they, when they are enthusiastically joining the LGBT revolution?

That 2000 CBF policy, still in effect, dates back to when an

older generation was leading the CBF and it reflects the fact that many of the

churches that were ready to join the CBF in the 1990 were not (yet) ready to

endorse homosexuality. The CBF has no argument against homosexuality on

biblical terms, so it is only a matter of time before it changes its policy.

Even in 2000, the group announced the policy but claimed to take no “position”

on homosexuality itself: “CBF values and respects the autonomy of each

individual and local church to evaluate and make their own decision regarding

social issues like homosexuality.”

Amazingly, a similar claim was made by Jim Dant, the pastor of

First Baptist Greenville. The church announced that it was officially ready to

ordain gay ministers and celebrate same-sex weddings, but the pastor told his

church “we made no decision regarding the issue of homosexuality.”

That is theologically, biblically, morally, and even logically

incoherent. The church most certainly did make a decision regarding

homosexuality. Every single member of that church is now a member of a church

that will accept same-sex couples as members, celebrate gay weddings, and

ordain LGBT ministers. That is making a decision.

The congregation assigned a LGBT Discernment Team, but there is

no evidence that the team made any effort to discern the Scriptures. Instead,

it discerned the congregation itself, determining that “being open and

welcoming to all is a part of the essential nature of our community of faith.”

There are big lessons here for every church, every denomination,

and every Christian institution. Once biblical inerrancy is abandoned, there is

no brake on theological and moral revisionism. The Bible’s authority becomes

relative, and there is no anchor to hold the church to the words of Scripture

and 2,000 years of Christian witness.

The discernment process at First Baptist Church in Greenville

offers us all ample lessons that should lead to a more fundamental discernment:

Without the affirmation that the Bible is inerrant, “discernment” leads to

disaster.