BETO O'ROURKE NEEDS TO THINK BEFORE HE SPEAKS ON SAME-SEX MARRIAGE. IN AMERICA, WE DON'T TAX CHURCHES INTO SUBMISSION

/arc-anglerfish-arc2-prod-dmn.s3.amazonaws.com/public/IESJYNCTWBG7U5RLACSW7BF2BU.jpg)

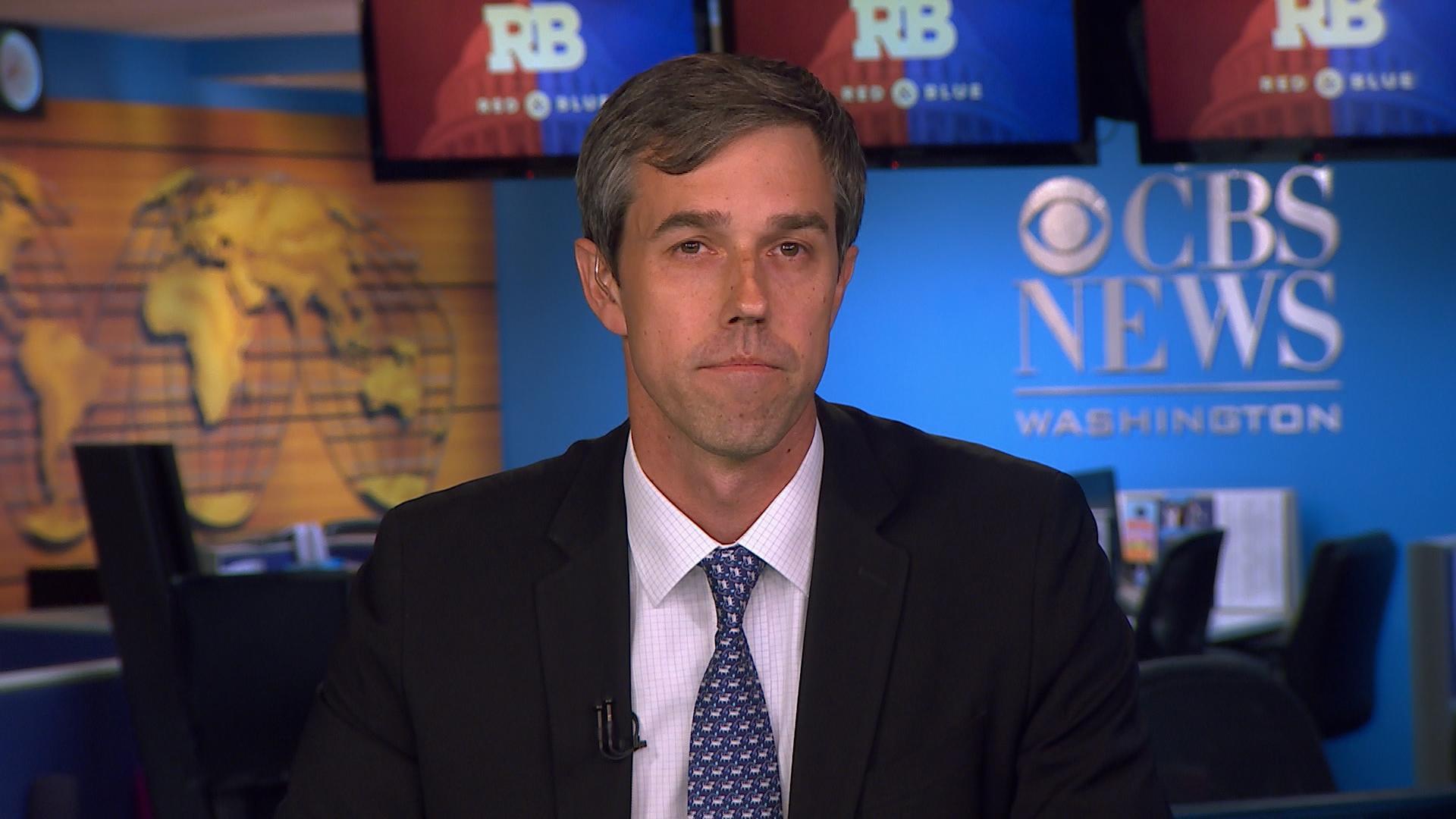

Former Congressman Robert Francis "Beto" O'Rourke isn't exactly setting the world on fire with his campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination. In an Emerson College poll of Democratic caucus-goers in Iowa conducted before and after the debate this week, his support was so low, it didn't even register. The man who was once considered the liberals' best hope for retaking a U.S. Senate seat in overwhelmingly red Texas is running so far in the back of the pack, he's in danger of falling out.

Now, he'll have to pander to the single-issue constituencies within the Democratic Party, as well as the 'pundit-crats' who fell in love with him during his Senate bid, for enough support to keep his campaign afloat.

That's probably why he answered unhesitatingly and in the affirmative when CNN's Don Lemon asked in a recent forum, "Religious institutions like colleges, churches, charities—should they lose their tax-exempt status if they oppose same-sex marriage?"

To be fair, he probably didn't think about the question very thoroughly before answering. He didn't consider all the implications inherent in his response for a nation like ours, which was founded, in no small way, as a sanctuary for those seeking religious liberty. But answer that way he did, and he has to accept he'll be criticized for it.

/https://static.texastribune.org/media/files/6b0f36df6e1a1d22ab2778b0fa23dfd8/04%201st%20Dem%20debate%20Beto%20REUTERS.jpg)

O'Rourke's answer reminded me of another political leader who, centuries ago, when confronted with an unresolvable conflict with the church over a different issue regarding marriage, chose to take matters into his own hands.

It's a complicated story, central to the storyline of the Academy Award-winning film A Man for All Seasons, that's not as well-remembered as it should be. In brief, King Henry VIII, unable to obtain a papal annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon, broke with Rome and established the Church of England with himself as the head. He then moved into the second of the many marriages for which he is infamous.

While this schism horrified church leaders and Catholics who continued to profess allegiance to Rome, others went along quietly, if not gladly, for economic reasons. Henry, as he moved forward to consolidate his control, seized church assets, bringing valuable land and other properties under royal control or, to put it more bluntly, taxed them into submission.

This is precisely what CNN's Lemon proposed, and O'Rourke supported, despite this country's long history of tolerance on matters of individual conscience and religious doctrine. The so-called separation of church and state, a phrase that appears nowhere in the U.S. Constitution but comes instead from a letter on the subject of religious liberty written by Thomas Jefferson to a congregation of Baptists in Danbury, Connecticut, exists to protect the church from the state and not vice versa.

Religious organizations are part of the dynamism that makes the nation what it is. It's an observation going back as far as Alexis de Tocqueville, if not further. They are a vital part of the national fabric and perhaps the only ones strong enough and well-funded enough to compete with the state in the delivery of what we now consider essential social services. Like the government, religious groups run hospitals, provide for the poor, educate the young, care for the old and engage in other activities without which the country might grind to a halt.

That they can do as much as they do to improve Americans' lives is in part because they are largely free of the burden of taxation imposed on individuals and businesses. To force them to turn over funds that would be used for good works, as punishment for not getting with the rest of the cultural elites on the doctrinal matter of the nature of marriage, would constitute an enormous constitutional and cultural overreach. Yet O'Rourke went there, even if he did later clarify his position, walking it back outside the area of doctrine and into the bright light of matters related to the delivery of public services. Can other Democrats who want to be president be all that far behind?

It used to be said that what was once called the "religious right" wanted to use the power of the government to impose its views on everyone else. Maybe—though I always found the allegation specious. Now, the pendulum is swinging. It is the secularists, whose views O'Rourke initially endorsed (again, one hope's without thinking), who appears to be driving the train in a way that could have profound implications for the future of America.

Peter Roff